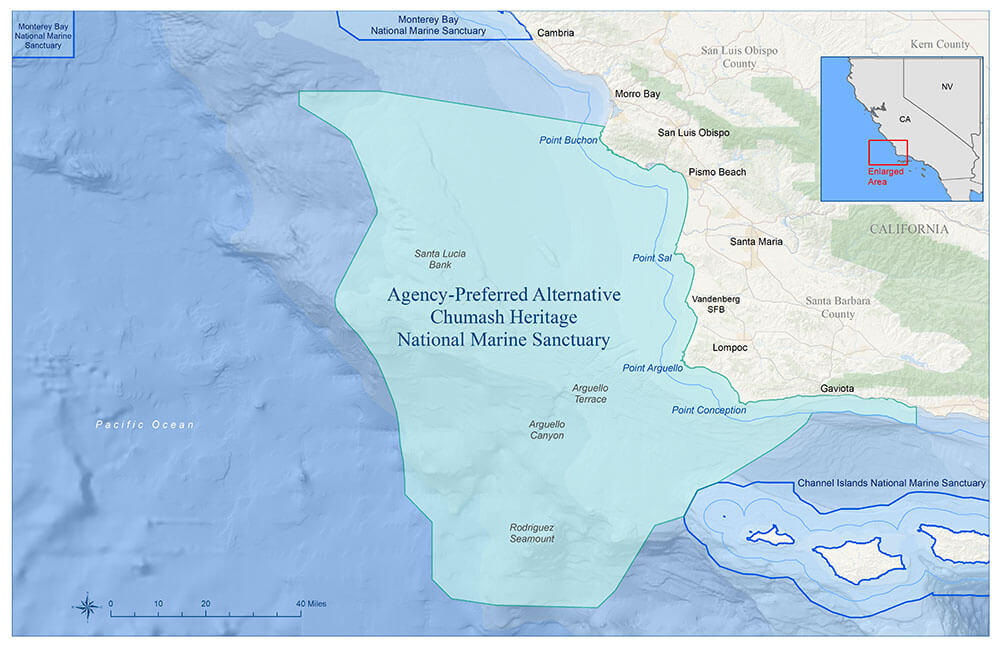

In a turn of events, boundary lines for the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary proposal, which would have closed the gap between the Monterey Bay and Channel Islands sanctuaries, revealed a gap that omits the Central Coast cities of Morro Bay and Cambria to make room for offshore wind development.

On October 25, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a federal agency authorized to designate national sanctuaries, closed the public comment period on the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary (CHNMS) proposal. The Northern Chumash Tribal Council members, who had envisioned a sanctuary including Morro Bay and Cambria, must now rely on public commentary to keep their original boundary lines intact.

The initial boundary would have covered 7,600 square miles and closed the gap between the Monterey Bay and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuaries, potentially protecting around 20,000 square miles of sea and coastline.

Instead, NOAA’s preferred CHNMS boundary for the Central Coast covers 5,600 square miles, from northern Montaña de Oro State Park to the Gaviota coastline, excluding an important site to the Chumash people and a popular tourist destination: Morro Bay.

“NOAA’s preferred agency plan was very disappointing,” said Mona Olivas Tucker, a tribal chairwoman for the YAK TITʸU TITʸU YAK TIŁHINI (ytt), Northern Chumash Tribe. “It came as a big surprise when it did happen. It took a while to understand what had happened and then to understand why it happened took some time, and then to try to decide, ‘Could we do anything?’”

Offshore wind is one reason for the decision to reduce the CHNMS boundary lines. The Biden Administration is pledging to disseminate 30 gigawatts of offshore wind nationally by 2030. NOAA claims that reducing the boundary would assist with subsea electrical transmission cables.

“It removes an area where a large number of subsea electrical transmission cables from offshore wind leases to the Morro Bay area that would likely be unprecedented in a national marine sanctuary,” NOAA stated.

In a press release from the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, NOAA received 98,721 public comments in response to their preferred CHNMS proposal. The comments represent over 100,000 individuals and organizations.

“This was the final chance for our communities to show up and say exactly what we want the sanctuary to look like,”Northern Chumash Council Chairwoman Violet Sage Walker said. “The overwhelming majority of commenters are joining us in saying, ‘We need the Chumash Sanctuary to protect the entire Central Coast from Cambria to Gaviota now!’” .

One major benefit of a national sanctuary is to prohibit offshore drilling and prevent disasters such as the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, resulting in an estimated 3 million gallons of crude oil being spilled into the ocean.

Michael Khus-zarate, a board member of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, remembers the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill.

“And I gotta tell you, that was a big deal on the Central Coast, huge,” Khus said. “It wasn’t just in Santa Barbara, a lot of people took notice of this.”

Khus, a teenager at the time and a member of the Junior Statesmen of America, was given the opportunity to interview then-California Governor Ronald Reagan during a speech given to the organization on the importance of democracy.

“What are you going to do about the oil spill?” said Khus, remembering what he asked Reagan during the interaction.“What he came back with was, ‘The best way to go ahead and prevent future oil spills is to pump all the oil out of the ground, and then you wouldn’t have any more oil to spill.’”

Due to national coverage of the Santa Barbara oil spill, the National Marine Sanctuaries Act was signed into law by former President Richard Nixon in 1972, which allows the CHNMS to be considered as a sanctuary today.

Khus said his mother, Pilulaw Khus, alongside other members of the tribal council, advocated for the marine sanctuary in the ’80s.

It wasn’t until Fred Harvey Collins, once leader of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, set out to create the CHNMS to be submitted to NOAA six years ago, that the sanctuary started becoming a reality. Collins will not see the results of his work, as he passed away on Oct. 1, 2021. He was 71.

That job has been passed down to his daughter, Violet Sage Walker, who has taken the leadership role her father once held.

Now that the public comment phase has come to an end, NOAA will review the proposal and make a final decision regarding the sanctuary in 2024.

“We’ve already basically started acting as if the sanctuary is already designated,” Khus said.

The Northern Chumash Tribe is teaming up with marine scientists to do field research along the coastline, said Khus. Marine biologist Stephen Palumbi from Stanford University is working with the tribe to better understand the biodiversity of the Central Coast’s marine life by collecting environmental DNA.

“It gives us a kind of census, so to speak, of what life forms populate our coastline,” Khus said.

As NOAA deliberates, the Northern Chumash Tribe is pressing forward with scientific collaboration and stewardship. Their proactive approach, combining traditional knowledge with modern science, honors the legacy of past leaders and keeps momentum going for a decades-long journey toward environmental and cultural preservation.