Films made by Studio Ghibli consistently capture a magic that no other media has been able to, particularly the films directed by one of the studio’s founders, Hayao Miyazaki.

At surface level, it’s easy to discern they are a cut above the rest when compared with other 2D animation, with Ghibli’s imaginative character designs, constant fluid motion, and immaculate attention to detail in every scene. This is especially apparent in crowd and establishing shots. Where lesser films would utilize tricks such as cutting detail and motion to make these shots quicker and easier to produce, Ghibli revels in them, giving equal attention to every moving piece, telling little stories and creating spaces that feel much more alive.

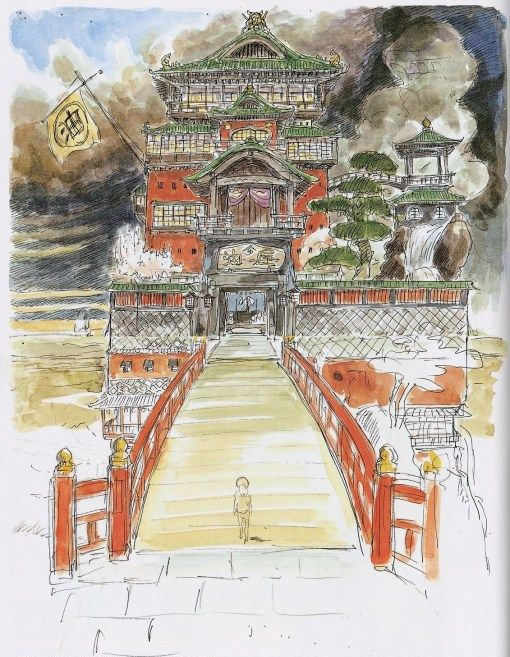

Visuals are also vital to the initial stages of crafting these films. Miyazaki is unlike other film makers in that he rarely, if ever, begins his creative process with a set script. Instead, he puts together a loose chain of events and focuses on creating fantastical moments first. All of the rough storyboards for any Miyazaki film begin life as a set of watercolor illustrations depicting crucial moments from the story with an emphasis on powerful imagery. Once this is achieved he goes back to fill in the gaps.

But the mark of a good film goes beyond visuals; equally important is sound design. The soundscapes of Miyazaki’s films have an enormous amount of range to them, able to create atmosphere and mood in an instant.

The serene and luscious environments of “My Neighbor Totoro†are full of very natural sounds, such as grass rustling in the breeze and countless bugs chirping. These natural aspects are brought to the forefront of the soundscape to further create the sense that this is a living, breathing world.

In comparison, the soundscape of “Princess Mononoke†is vastly different, despite being every bit as nature focused. Where the sounds of life and nature evoked serenity in “Totoro,†here they create tension; the stillness of the forest often disrupted by the chugging of ironworks, the howls of distant wolves, and the booming conflict of battles too close for comfort. Through its sound, it’s quickly discovered that in “Princess Mononoke,†this is a much harsher world.

These living and breathing soundscapes are pushed to their furthest in 2013’s “The Wind Rises,†Miyazaki’s final film at the time of writing. While every other Ghibli film thus far had used incredibly detailed and realistic sounds to create a living atmosphere, this film took this concept beyond that to be literally living and breathing. Every non-musical element here was recorded by a single person making these sounds with his mouth, Koji Kasamatsu, from the engines of planes sputtering to life to the shallow whistle of the wind itself.

This unique creative decision accentuates the mind and perspective of the film’s protagonist, Jiro, a plane designer who is constantly daydreaming about his designs, often so caught up in his thoughts that he fails to realize what’s going on around him.

Equally as compelling in terms of sound are the original soundtracks composed for each Miyazaki film by Joe Hisaishi. Hisaishi’s music tends toward big orchestra sounds, but has an impressive range. Whether a scene is meant to feel triumphant and celebratory, or grim and imposing, the score for each moment matches perfectly.

That’s not to say that the soundtrack is used as a crutch to establish these moods; soundtracks here are much more of an accessory than a focus. It’s not uncommon for stretches of six to eight minutes to pass in a Ghibli film without any music at all, the spaces in between allowing the previously mentioned soundscape to establish particular feelings about a scene. Along with the visuals, these provide a sort of base that the music can build off of and accent.

The final element of the quintessential Miyazaki film I want to cover here is the storytelling, which will be divided into two key pieces: active viewer participation, and allowing the film to breathe. These two qualities are key to how these films manage to so strongly resonate with so many people.

In Ghibli movies, a certain involvement is demanded of the viewer. Rarely will a scene be completely straight forward in telling viewers how to feel about a character or an event. No character on screen will ever be pronounced the “bad guy,†or commit heinous acts simply for the sake of it.

Even the main protagonists in most of these films trend toward a bit of ambiguity and fluidity in their character, never acting as a perfect stand in for the viewer. The characters possess clear intentions that we don’t necessarily have a full grasp on. There’s a sort of ambivalence present in most scenes, a sense that every character on screen knows who they are, what they want, and why they are where they are; to assess and judge is left to the viewer.

This is most clear in 1997’s “Princess Mononoke,†where after a skirmish with a demon, Ashitaka, the protagonist, is forced to travel to the west to “see what you can see with eyes unclouded by hate.†This line defines his journey and the people and creatures he meets. Whether it be a kindhearted yet greedy and conniving monk or a vicious wolf god trying to protect what’s left of her forest, the characters he encounters are portrayed as not good or evil, but as conflicting perspectives with differing but equally valid motivations.

The shining example within the film comes once Ashitaka reaches Iron Town and meets Lady Eboshi. Although indirectly, she is responsible for creating the demon that forced him to leave his home. Additionally, her group is actively destroying the forest and killing the creatures in it in order to create more iron and increase the town’s wealth, directly in conflict with the wolf god mentioned previously.

If there were going to be a traditional antagonist, Eboshi would be it, and for a moment the audience comes to this conclusion too. However, within the same ten minutes that we learn these terrible things, we also learn that Eboshi uses the funds from the iron to buy the contracts of brothel girls from the city, freeing them and letting them start new lives in Iron Town. Eboshi also takes in and cares for lepers, letting them contribute to the town by designing tools and weapons despite having been rejected from the rest of society.

The way that Lady Eboshi is presented is multifaceted and difficult to pin down as good or evil. The two sets of actions shown seem to directly contradict each other morally and exist in a sort of muddy grey area.

On top of this, all of these scenes are careful never to show Ashitaka’s reaction to these revelations, ensuring that the viewer will decide for themselves how to feel about Eboshi and Iron Town. These sorts of nuanced and involved moments are present throughout all of Miyazaki’s major works. They reward a consciousness and awareness from viewers, asking viewers to take an active role in what’s happening on screen.

Finally, the other key aspect of Ghibli films centers is pacing. Many modern movies tend towards storytelling through constant action, characters being proactive at all times, always moving towards their goal. Rarely are characters allowed to breathe and to process. Miyazaki’s films show that it can be very humanizing and refreshing to step away from the action and rest for a moment.

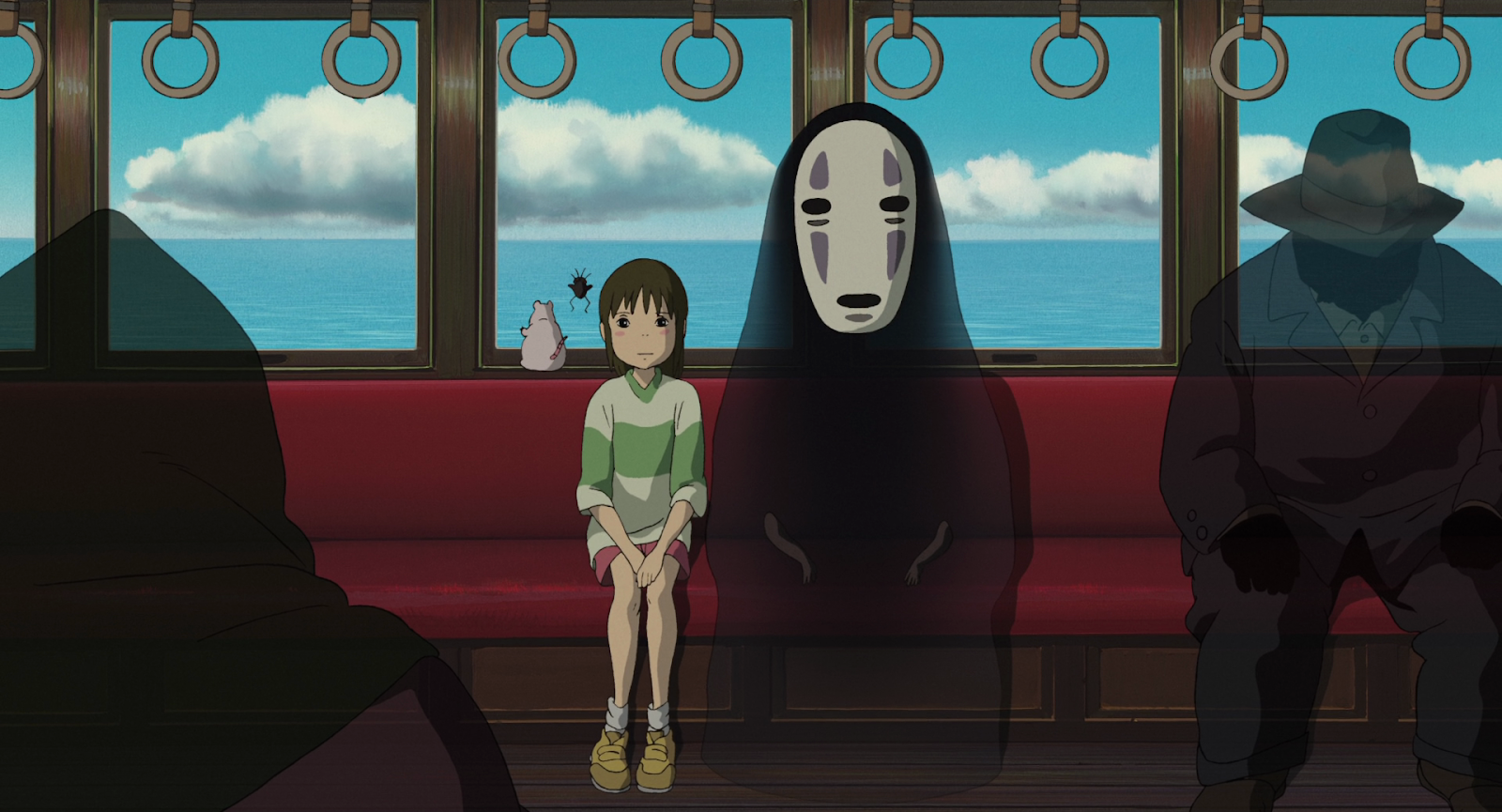

This is best shown in the train scene in 2001’s “Spirited Away,†after a hefty amount of action in the spirit bath house where Chihiro, the protagonist, has been working. After having learned the truth of her friend Haku’s suspicious actions, having faced her employer’s terrifyingly powerful sister, and having been chased by a giant ravenous spirit known as “No Face,†Chihiro sets off on a one way train ride to Swamp Bottom to make things right.

The events mentioned were fast paced, thrilling, and had high stakes. They gave the viewer a lot of information in a short amount of time and were very involved. In contrast, the scene that follows on the train is nearly eight minutes of breathing room before the story picks up again. Chihiro sits beside faceless spirits as the endless sea around her flashes past, the occasional island or train station sprinkled in, neon signs eventually taking their place as night falls.

Technically speaking, nothing is accomplished, but what this scene does is vital to the pacing of the film. It allows the viewer to process all the action they just watched, to soak it in and draw their own conclusions about it, and to prepare for what comes next.

It’s an aspect of pacing that is often downplayed in storytelling, and it’s one that Miyazaki has a masterful grasp of. I would go so far as to say it’s the core of what makes these films so magical.

While I’ve done my best to outline some of the reasons these films are so special to me, there are countless more endearing and magical qualities I haven’t even scratched the surface of. Given the fantastical worlds and creatures, the superb symbolism and thematic depth of each film, and some of the most believable heroines in fiction, there’s a lot left to love about Miyazaki’s work.

However, this magic is something best experienced firsthand. The full Ghibli collection is currently streaming on HBO Max. I implore everyone to give these films a watch if you haven’t and a rewatch if you have. My personal recommendations would be “Spirited Away†and “Princess Mononoke,†as they are the most standout films the studio has produced in my opinion, although “Porco Rosso†holds a special place in my heart too. If you want something a little more lighthearted or kid friendly, however, I recommend “Ponyo†and “My Neighbor Totoro.â€

Animation is too often written off as childish, simple, and lesser than traditional filmmaking. However, with the works of Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

See what you can see with eyes unclouded by hate.

Taylor Saugstad • Mar 25, 2021 at 3:26 pm

This is a great piece. Glad to read an in-depth article about Studio Ghibli.