Southern sea otters in San Luis Obispo County are dying from a rare and aggressive strain of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii.

The parasite originates from a host seemingly removed from the sea otters’ ocean habitat. Although T. gondii can infect all warm-blooded vertebrates, it can only reproduce in cats. This means that although it can be transported through consumption of food and water contaminated with the parasite, T. gondii depends on wild and domestic cats as its primary host in order to breed.

T. gondii infection in sea otters has been studied by scientists for decades. Research shows that 62% of sea otters are infected with this parasite, and it was found to be the primary or contributing cause of death for 8% of sea otter deaths recorded from 1998-2012.

One of the reasons that scientists are so interested in T. gondii infection in sea otters is because humans are also susceptible to it. About one-third of the global human population is believed to host T. gondii.

Research indicates that the parasite may cause behavioral changes in its hosts, which include demonstrating a stronger inclination toward taking risks.

Manipulating host behavior could be an evolutionary tool for T. gondii. Risk-taking behavior may benefit the parasite by creating increased chances of it being able to infect more hosts. For instance, a rodent infected with T. gondii may be more likely to approach a cat because its fear has possibly been diminished by the parasite itself.

T. gondii gets into the environment by cat feces being flushed into freshwater drains, streams and rivers, either by large rain events or people flushing cat litter down their toilets. Traditional wastewater treatment plants do not typically remove T. gondii, and as a result, active spores continue to be released into waterways. The spores flow out to the ocean and are then accumulated by filter feeders like mussels and clams, which siphon water and concentrate this pathogen.

Otters consume mass amounts of these filter feeders every day in order to maintain their metabolism, so they are generally exposed to a heavy dose of T. gondii. Symptomatic otters show neurological issues, such as tremors. If they die, and a necropsy is performed, scientists typically find the parasite embedded in their brains.

In February 2020, a stranded sea otter that washed up dead on a beach in San Simeon alarmed researchers.

Michael Harris, an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, collects and studies dead sea otters in the San Luis Obispo area with the help of The Marine Mammal Center. Upon necropsy of this particular sea otter, Harris discovered the parasite not just in its brain, but as a systemic infestation throughout its entire body.

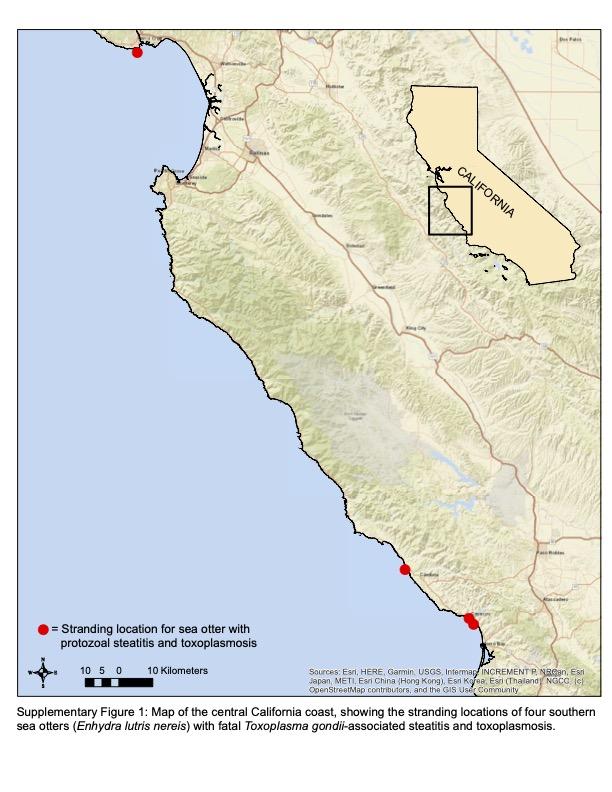

In a 2023 research article titled, “Newly detected, virulent Toxoplasma gondii COUG strain causing fatal steatitis and toxoplasmosis in southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis),” several scientists, including Harris, wrote a collaborative paper about their findings. At the time of publishing the report, four sea otters had been found infected with this strain of T. gondii.

Since this 2023 report was published, several more sea otters in San Luis Obispo and Santa Cruz Counties have been found infected with this strain.

“A very important distinction here is this is the first-published account of a rare genotype of Toxoplasma that we discovered in sea otters that has quite an unusual presentation and is very pathogenic,” Harris said.

The discovery of this genotype showing up in California’s Central Coast is alarming because before these recent sea otter discoveries,, the only time it had been detected was during a 1995 human outbreak of Toxoplasma in British Columbia, Canada. The outbreak’s source was traced back to two mountain lions, which resulted in this rare genotype being classified as the COUG strain.

Although most people are asymptomatic, immunocompromised and pregnant women should be especially careful to avoid infection. Individuals can take special precautions so that they do not ingest the parasite.

“Eat produce that is cleaned well,” said Dr. Elizabeth Lobo, a professor in the Biological Sciences department at Cuesta College. “Eat meat that has been frozen and/or is cooked thoroughly. To avoid the COUG strain, in particular, do not consume seafood (unless frozen adequately and or cooked thoroughly) from areas where this strain has been identified.”

An important step that individuals can take to help stop the spread of T. gondii is to follow these best practices for disposing cat litter, which includes focusing on never flushing feline waste down the toilet.

Devinn Marie Sinnott is a veterinary pathologist who is currently a Ph.D. candidate focusing on Sarcocystis neurona, a parasite that is related to T. gondii but is shed by opossums. Sinnott has experience with T. gondii because sea otters are often infected with both parasites. Sinnot recommends that domestic cats stay indoors so that they do not contaminate the environment with their feces.

“Climate change drives these atmospheric rivers and really heavy rainfall, and with all of the surface water that we accumulate during these heavy storm periods, cat poop from nowhere near a river can wash out to the ocean,” Sinnott said. “Climate change is driving changes in water transport and precipitation changes, leading to differences in freshwater runoff.

“Humans have changed the landscape, like getting rid of wetlands, which normally act as natural filters for pathogens like Toxoplasma,” Sinnott continued. “Keeping wetlands intact and trying to combat climate change could help with this issue.”

Individuals can help by informing themselves about local watershed issues and projects, and considering volunteering for The Marine Mammal Center.